By Dennis Thompson

HealthDay Reporter

Extremely tiny bits of plastic: They’re in your food and drink, and even in the air around you, reported HealthDay News (June 5, 2019).

Now, new research calculates that the average American consumes more than 70,000 particles of these “micro-plastics” every year — and even that’s likely an underestimation, the scientists noted.

Your micro-plastic intake might be even higher if you choose products that have more plastics involved in their processing or packaging — including bottled water, the research team said.

Just how harmful is all this plastic in your body? That’s still unclear, said one expert unconnected to the new study.

“It’s certainly concerning,” said Dr. Kenneth Spaeth, chief of occupational and environmental medicine at Northwell Health in Great Neck, N.Y. “I think the best we can say is perhaps there’s minimal harm here, but I think there is a possibility the harm could be extensive.”

Other recent studies have shed light on the ubiquity of micro-plastics in people’s bodies.

For example, one report out of Austria found that the average human stool sample contained at least 20 bits of micro-plastic. In another study, micro-plastic was found in 90% of samples of common table salt.

However, it’s tough to accurately calculate the amount of plastic people consume, noted the lead author of the new study, Kieran Cox. That’s because the 26 studies used in the evidence review involved food sources that only reflect about 15% of people’s daily diet, he noted. Cox is a Ph.D. candidate with the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

The researchers added that a person’s micro-plastics consumption rises based on personal food choices they make. For example, a person who only drinks bottled water could be ingesting an additional 90,000 micro-plastics annually, compared with just 4,000 micro-plastics for someone who only drinks tap water.

That shows how “simple choices may drastically alter your exposure to plastics,” Cox said.

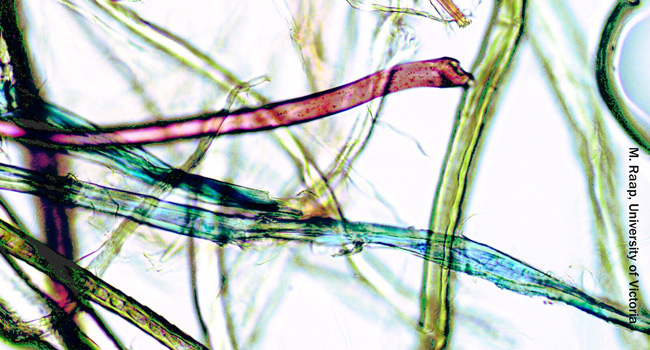

Micro-plastic particles are incredibly tiny, less than 130 microns in diameter. For comparison, a human hair has a diameter of about 50 microns.

In the new study, Cox and his colleagues analyzed more than two dozen studies that estimated the average micro-plastic content of different types of foods.

They then estimated what an average person’s micro-plastic intake would be if they ate the recommended daily amount of these foods.

The studies included in the review focused on such commonly consumed items as seafood, sugar, salt, honey, alcohol and bottled water, Cox said. A whole host of other common foods, including chicken, deli meats, vegetables and dairy products, have not been analyzed for their micro-plastic content.

“We don’t have a huge part of the puzzle,” Cox said. “We have a small portion of it. We know these are underestimates.”

Based on these studies, the researchers estimated that annual micro-plastic consumption ranges between 39,000 to 52,000 particles, depending on age and sex.

If micro-plastic particles inhaled via breathing contaminated air are included in the estimate, the annual load increases to between 74,000 and 121,000, the team said.

The numbers would likely be higher for people who eat foods and drink liquids that are processed using plastics or packaged in plastics, Cox added.

For example, studies show that tap water exposes people to between 3,000 and 6,000 micro-plastic particles each year, but bottled water exposes them to between 64,000 and 127,000 particles annually if that’s their only water source.

That’s because bottled water is exposed to plastic in a number of different ways, both during processing and as it sits in its plastic bottle waiting for someone to take a swig, Cox said.

There’s no clear handle yet on how these plastic particles could affect human health, Cox and Spaeth said.

“The extent to which it is posing a health risk is uncertain at this point,” Spaeth said. “There’s very little data in the way of human studies that look at health effects in any way.”

There’s a chance that harmful chemicals in the plastic might leach out of the particles as they pass through the body, Spaeth said.

Some particles also might lodge in the body following inhalation or ingestion, causing immune system responses and cellular damage, the researchers added.

“Once in the lung, depending on the size of the particle, it could conceivably pass into the circulation and go anywhere in the body,” Spaeth said. “This study points out there’s an accumulation of these particles at pretty high numbers.”

The findings were published June 5 in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

New breast cancer drug ups survival rates

A new form of drug drastically improves survival rates of younger women with the most common type of breast cancer, researchers said on Saturday, citing the results of an international clinical trial. The findings, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago, showed that the addition of cell-cycle inhibitor ribociclib increased survival rates to 70 percent after three and a half years.

The mortality rate was 29 percent less than when patients, all under 59 and premenopausal, were randomly assigned a placebo.

Lead author Sara Hurvitz told AFP the study focused on a form of breast cancer which is fueled by the hormone estrogen and which accounts for two-thirds of all cases among younger women. It is generally treated by therapies that block the hormone’s production.

“You actually can get synergy, or a better response, better cancer kill, by adding one of these cell-cycle inhibitors” on top of the hormone blocking therapy, said Hurvitz.

The drug works by inhibiting the activity of cancer-cell promoting enzymes. The treatment is less toxic than traditional chemotherapy because it more selectively targets cancerous cells, blocking their ability to multiply.

An estimated 268,000 new cases of breast cancer are expected to be diagnosed in women in the U.S. in 2019, while the advanced form of the disease is the leading cause of cancer deaths among women aged 20 to 59.

Though advanced breast cancer is less common among younger women, its incidence grew two percent per year in the U.S. between 1978 and 2008 for women aged 20 to 39, according to a previous study.

The new trial, which looked at more than 670 cases, included only women who had advanced cancer – stage four – for which they had not received prior hormone-blocking therapy. “These are patients who tend to be diagnosed later, at a later stage in their disease, because we don’t have great screening modalities for young women,” Hurvitz said.

In addition, patients who develop breast cancer early tend to have more complex cases.

“That’s what makes us so excited, because it’s a therapy that’s affecting so many patients with advanced disease,” added Hurvitz.

A pill is administered daily for 21 days followed by seven days off to allow the body time to recover, since two-thirds of patients have a moderate to severe drop in white cell count.

Jamie Bennett, a spokesperson for Novartis, which markets the drug under the brand name Kisqali and funded the research, said it cost $12,553 for a 28-day dose.

But, she added, “the majority of patients in the U.S. with commercial insurance will pay $0 per month for their Kisqali prescription.”

There is no cure for metastatic breast cancer and the majority of the women on the drug will require some form of therapy for the rest of their lives.

Oncologist Harold Burstein, who was not involved in the research, said it was “an important study,” having established that the use of the drug “translates into a significant survival benefit for women.”

Burstein is with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“Hopefully, these data will enable access for this product for more women around the world, particularly in healthcare systems which assess value rigorously as part of their decisions for national access to drugs,” Burstein added.

Moving forward, Hurvitz said she was interested in investigating whether ribociclib could help nip cancer in the bud at an earlier stage.

“We want to go and look at those women diagnosed with early stage disease, small tumors, tumors that haven’t gone to the lymph nodes or haven’t gone to other parts of the body and see if we can stop it from returning later from metastasizing,” she said.

The enrollment phase of new global clinical trial is now underway.