For the first time, biologists have been able to document how two common respiratory viruses fuse together to form a hybrid capable of bypassing the human immune system and infecting lung cells. Scientists believe their work will help explain why co-infection, for some patients, significantly aggravates the course of the disease and makes it more difficult to treat.

Up to half of all cases of acute respiratory infections are mixed infections, in which the human body has to fight several pathogens at the same time. Most often, the viruses either simply coexist with each other or oppose each other. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can affect the lower respiratory tract and can cause bronchiolitis with acute respiratory failure in children. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, this infection accounted for a large proportion of cases of severe acute respiratory infections, sometimes requiring ventilatory ventilation. RSV is characterized by its involvement in miscellaneous infections, but the molecular mechanisms and causes of such acute respiratory infections are still unclear.

Virologists at the University of Glasgow, led by Pablo Murcia, decided to study what happens to cells when simultaneously infected with respiratory syncytial virus A2 and influenza A/H1N1. They incubated cultures of human bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells with both pathogens, then studied cell changes 12-72 hours later.

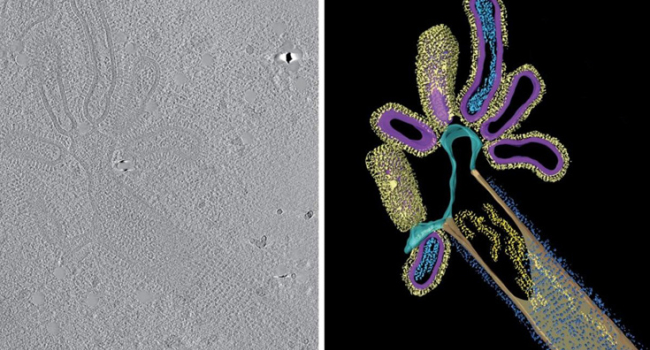

The scientists found that instead of competing with each other, they fused together to form a palm-shaped hybrid virus. RSV became the “trunk” of this “palm” and the “leaves” were the flu virus. No one had previously described such hybrid viruses, according to Pablo Murcia.

Viruses from two completely different families combined together to form a new type of pathogen that can infect neighboring cells, even in spite of the presence of antibodies to influenza. The antibodies graft onto the flu proteins on the surface, but the virus simply uses the free proteins from the RAV to infect the cells. As Murcia said, the flu used the hybrid viral particles as a Trojan horse.

According to virologist Dr. Stephen Griffin of the University of Leeds, such collaborative work could increase the chances of a deadly disease, viral pneumonia.

The next step is to prove that hybrid viruses can appear in patients infected with two infections at once, and to test which virus pairs are capable of doing so.